“Love requires sacrifice.”

Initially set in 1992, then jumping to the present day, Bryce McGuire’s Night Swim centers on a residential pool situated in the backyard of a peaceful, welcoming home in an affluent Twin Cities neighborhood. Fed naturally by a nearby spring, the pool is the ideal addition for anyone who longs for summer cookouts and those peaceful, late-night swims.

Enter the Waller family.

Ray (Wyatt Russell), a former prolific third baseman for the Brewers, is battling stage two MS, a condition that attacks his nervous system. He and his wife Eve (Kerry Condon) are looking for a place to rest and rehab as he processes his life without the sport that has been his identity since childhood. After a series of test results show advancing conditions, Ray is encouraged to try water therapy. A house with a pool suddenly appears to be the perfect acquisition.

Or so the family thought.

Agonizingly slow and disjointed, McGuire fails to expand on the film’s source material, a 2014 short he wrote and directed. The characters, painfully one-dimensional and, to a degree, unlikable, struggle to find a cadence, maneuvering their way through the movements as they deal with the sudden shift in their daily routine.

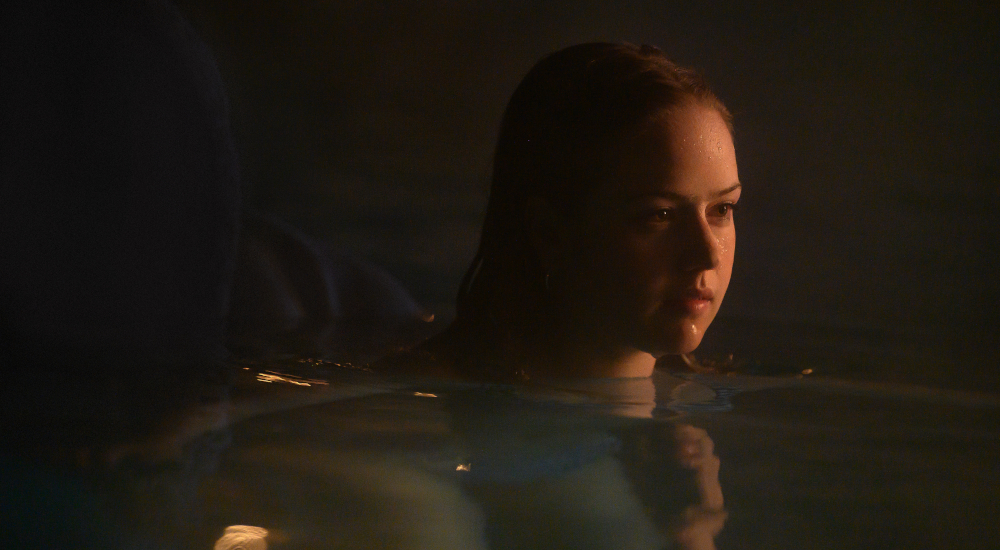

Though McGuire never sets the season, and life events conflict with one another to make the story’s placement unrealistic, viewers tag along as the family moves in and begins to rehab the pool. Before long, they are screaming as they jump from the diving board, immersing themselves in search of coins at the bottom of the deep end.

Life appears great. The family, as a unit, seems to be adjusting well.

As Ray begins to show signs of improvement, he attends one of his son’s baseball practices, offering up advice as the players, one by one, take turns at the plate. Short antidotes see sudden improvements in the kids as Ray’s expertise of the game helps each find their inner Barry Bonds. But when Ray is invited to take a swing, unleashing his newfound strength on a pitch, sending it crashing into the light pole in center field, those in attendance look on in amazement. And rightfully so. A man suffering from a neurological disease, without a moment of warmup, just took the cover off a ball.

But the instant, unique and essential within the context of the story, is quick and short-lived. And like many others, McGuire never returns to examine or explain the phenomenon. Instead, our characters continue with their new routine, excited for Ray’s progress but never providing a sense of curiosity as to why the medical miracle is happening.

From a narrative perspective, many missed opportunities exist to dive into the characters and uncover the pool’s secret from within. Instead, we receive a sporadic splash of jump scares, an overdone pool party, and a manipulative realtor who obviously knows more than she lets on. But beyond Condon’s performance and a handful of creatively captured underwater sequences, there is very little to get excited about here.

After the pool party, when Eve decides she wants an answer to the mysterious occurrences happening with the pool, she seeks out a former resident with a history of the place. The conversation, the most tense of the film, shows the possibilities hidden within the cracks of the story. That potential, seeping out in micro chunks, provides a small tease of what Night Swim could have been. The intrigue it could have provoked.

But in the end, McGuire’s film is neither scary nor physiological. It’s hardly interesting and painfully familiar. While certain shots reminded me of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, most of the film brought back the horror of M. Night Shyamalan’s struggles, most prominently Lady in the Water and The Happening. And that, unfortunately, is not a compliment.