Recently, Luc Besson has been outsourcing his particular

brand of eighties-style action to a seemingly endless stream of protégés while

he makes clumsy attempts at artistic credibility (Angel-A) or alternate forms of blockbuster potential (the very

French Arthur films). No matter, Besson's best instincts have

always been the distinctly masculine, and filmmakers such as Pierre Morel (Taken and the undervalued From Paris With Love), Louis Letterier

(the Transporter franchise and the

masterful Unleashed), and now with Lockout, the team of Stephen St. Leger

and James Mather have taken up the reins of Besson's exuberant, face-punching

nonsense. Don't read nonsense as a

pejorative there.

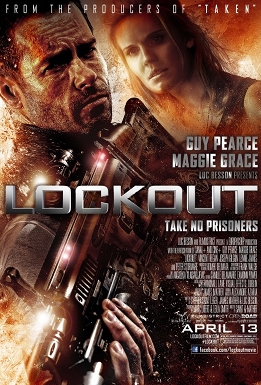

Essentially a retread of Escape

From New York in space, Lockout opens

with a series of comic-book ready set pieces wherein somehow Snow (Guy Pearce,

playing Kurt Russell), a government agent of some sort (and who cares about

details, really) is set up for a murder he didn't commit, and his partner

carrying the exonerating evidence (in a briefcase, natch) is sent to orbital

prison facility MS-One.

Conveniently, the President's bleeding heart liberal daughter, Emilie

(Maggie Grace), is kidnapped and taken hostage on MS-One while, in a piece of

classic Besson politicking, negotiating for prisoner's rights. Snow is sent to rescue her from the

exclusively Scottish criminals and find the MacGuffin.

Mather and Leger wisely structure the film as little more

than a series of escalating set pieces and breaks are only allowed for Snow to

crack a joke. This is the second

time Maggie Grace has been kidnapped in a Besson production, and although she's

occasionally given more agency than being consistently drugged and abused as in

Taken, Besson et al still take every

opportunity to crack a joke at her expense (women don't understand directions!

Hah!) Still, Emilie is among the

film's very few females, and the only one with more than two lines, and despite

the casual misogyny that is so typical of the genre, it's nice to see the film

avoid explicitly sexualizing (in the style of Bay) or, worse, threatening the

"purity" of the character (as in Taken). Not that the character does much at all, really, but it's

consistent with the film's old-school aesthetic that the feminine touch "“

indeed, sexuality of any sort "“ is conspicuously absent. Lockout

is a bit brain-dead, but it's refreshingly earnest and free of the cynicism

that has been seeping into Hollywood's product-placement blockbusters of late.